sm

smCOLUMN SEVENTY-FIVE, SEPTEMBER 1, 2002

(Copyright © 2002 Al Aronowitz

SECTION FIVE

sm

sm

COLUMN

SEVENTY-FIVE, SEPTEMBER 1, 2002

(Copyright © 2002 Al Aronowitz

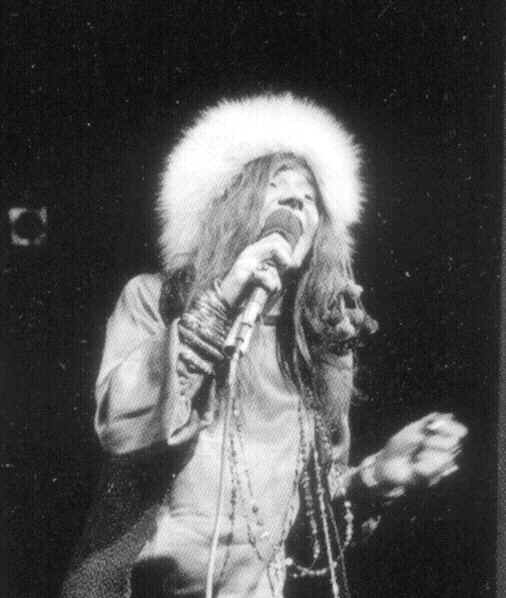

RETROPOP SCENE:

'CALL ME PEARL'

JANIS JOPLIN

(Photo by Amalie R. Rothschild)

They

told Janis not to blow it but she lived

her life the way a Hell's Angel rides his motorcycle. The Hell's Angels? She

loved them, too.

"You

don't have to be black to know how to sing the blues," she once told me.

"You just have to suffer. A

white person can feel suffering just as much as a black person."

In

the end, she was one of the highest-paid women ever to rent out

her soul to an audience, but if suffering is what she had to pay for her fame,

she never really came away with a profit.

Janis wasn't the prettiest girl in the world but she could look in

the mirror and like what she saw. Better

than anything, she liked being in bed with a man.

Better than anything except being onstage.

"That

40 or 50 minutes I'm out there, that's when it happens for me," she used to

say. "It's like fucking. It's

like having a hundred orgasms with somebody you love."

They told her

that she drank too much and so she changed brands.

"The

people who make Southern Comfort, they ought to send me free whiskey because I'm

such a good advertisement for them," she used to say. I remember once she

switched to Kaluha and milk because "It makes me feel like I'm drinking

some kind of health drink."

Still, she used to worry about what her mother thought of her. In the end, she tried to get away from the hard-drinking image that went along with being the best woman blues singer of her time. In the dressing room at the Summer Festival for Peace at Shea Stadium that August, I saw

Janis

was found dead

only three days

after Jimi Hendrix's funeral

her take a photographer's camera away and crush his film

beneath her heel because he had snapped her picture with a bottle in her

hand.

"I

call that fucked!" she said.

I was backstage

at San Francisco's Winterland Arena when the word filtered in that Janis had

been found dead in her motel room in Hollywood. It was only three days after

Jimi Hendrix's funeral, and the news was too incredible to provoke

anythinq but numbness. Some girls began to cry.

"What can

you do?" said Jerry Garcia, the guitarist-leader of the Grateful Dead.

"You just have to keep on." The Jefferson Airplane was in the

middle of its set, part of a concert with the Dead and Quicksilver to inaugurate

a series of programs at Winterland to challenge the dominance of Bill Graham and the Fillmore West over the music scene in the Bay Area.

It

started out as a festive night, broadcast live over one television channel and

two FM radio stations, but Janis' death took the heart out of the party.

The 7,000 who packed the hall didn't learn what had happened until after

the show was over.

"We

didn't want to make any announcement," said producer Paul Baratta,

"because the feeling was that this was a party and Janis was so much a part

of the scene that she would have understood that it would have been too

much of a downer."

When

the Jefferson Airplane came offstage, Grace Slick couldn't believe the

news. "Is it true?" she

said. "Is it true?"

Of all the names

made famous by the San Francisco music eruption of 1966, Janis' name was

probably the greatest. Like Billie

Holiday, she had all the earthy qualities of a whorehouse singer and yet

the subtleties of her voice revealed an artistry that made her an original in a

field cluttered with imitations. She

sang from a throat blasted by cigarettes, whiskey and dope, and yet out

of the gravelly rasp you could hear, if you listened closely, that her

voice had the unnatural quality of being able to hit two different notes at the

same time.

It was on the

stage of the Winterland, as well as on that of Bill Graham's original Fillmore

auditorium, that Janis first became a star singing with a group called Big

Brother and the Holding Companv. She had come to San Francisco from Port Arthur,

Texas, the city in which she was born on January 19, 1943, but which she felt

had rejected her because she liked poetry and the blues, had long

hair and because, as she said, "I didn't hate niggers."

"I hate that town," she used to say. But it was a hate tempered by contempt. There was an August 15 when she went back to Port Arthur for the 10th reunion of her graduating class from

Janis

became

a national star even before

she had a hit record

Thomas Jefferson High School "just to jam it

up their asses," she told me. "I'm

going to go down there with my fur hats and my feathers and see all those kids

who are still working in gas stations and driving dry cleaning trucks

while I'm making $50,000 a night."

Janis

became a national star even before she had a hit record, a legend even before

she became a national star. At the

Monterey Pop Festival in 1967, her performance with Big Brother was so

sensational that she became San Francisco's most sought-?after performer.

Afterwards, Albert B. Grossman, one of the most prominent managers in

contemporary music, took over her career and signed her to a contract with

Columbia Records. Actually, the

contract was with Big Brother and the Holding Company but when the group's

first album was released, Janis proved too formidable a star not to emerge as a

solo performer.

"She

had a great love of life," Grossman said afterwards.

"It's to; bad she didn't get to use that love in her own life.

I'll miss her. I loved her."

Janis went

through several different bands after separating from Big Brother to go

on her own. With each band, she had

to suffer criticism, even from within her own organization, but what the

criticism always boiled down to was the fact that she was too heavy to carry the

sidemen she chose. She called her

most recent group the Full Tilt Boogie Band and she was in the middle of

recording an album with them at the Columbia studios in Hollywood when her tour

manager, John Cook, found her body in her room at the Landmark Motel about 7

p.m. on the night of October 4, 1970. She was all of 27 years old.

"She had finished a session on

Saturday night and then had gone to Barney's Beanery with a couple of the

guys," Cook said. "Afterwards,

she drove her organ player back to the motel, said goodnight and then went to

her room. She was supposed to be

back in another session Sunday night and when she didn't show, I went to her

room. I had made up my mind that

nothing was wrong. When I got

there, I saw her car was still parked. I knew she was supposed to pick up her

boy friend at the airport, but I still kept telling myself that nothing was

wrong. So I thought I'd take her key and walk right in and find that she was

just off someplace. When I got inside I found all my preconceptions were wrong.

She had been getting ready for bed when she

died."

An autopsy was

held to determine the cause of death. Police

said they found fresh needle marks on Janis' arm, but Cook said Janis? old

needle marks still hadn't healed. Of

course Janis had been into dope, but it was said she had quit the previous

February.

"She was

really happy," Cook said. "She

was happy about her new boy friend, she was happy about her album.

The only thing bringing her down was Jimi." Janis was on the same

wavelength as Jimi Hendrix.

The last time I

saw Janis was at the Shea Stadium peace festival. I will always remember her running out to the stage, an

unannounced, surprise addition to the program.

At the time, I wrote that she reminded me of a star football player

running in to save the game.

Janis

was one of the few artists around who really knew how to handle an audience.

The last thing she told me was that she didn't like the name Janis any

more.

"I'm

sick and tired of it," she said.

"Call me Pearl."

She

certainly was a pearl. ##

CLICK HERE TO GET TO INDEX OF COLUMN SEVENTY-FIVE

CLICK HERE TO GET TO INDEX

OF COLUMNS

The

Blacklisted Journalist can be contacted at P.O.Box 964, Elizabeth, NJ 07208-0964

The Blacklisted Journalist's E-Mail Address:

info@blacklistedjournalist.com

![]()

THE BLACKLISTED JOURNALIST IS A SERVICE MARK OF AL ARONOWITZ